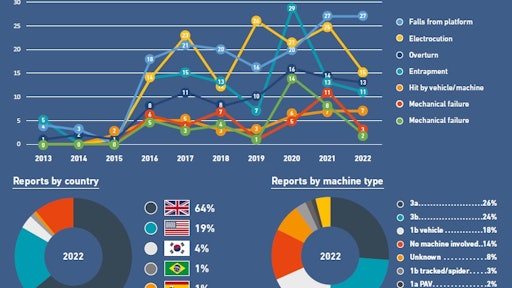

Accident data involving mobile elevating work platforms (MEWPs) has been monitored for decades.

A notable report issued by the Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR), covering the U.S. between 1992 and 1999, stated that an average of 26 construction workers die each year from using aerial lifts—this comprised 2-3 percent of all construction deaths. The report detailed the causes of deaths in construction by type of MEWP and identified the leading causes of the accidents to be electrocutions, falls from the platform, machine tipovers, being caught in or between (crushing) and being struck by or against.

To help prevent such accidents in the future, the International Powered Access Federation (IPAF) has been reporting on accidents involving MEWPs since 2012.

In IPAF’s 2023 Global Safety Report, the data shows that top of the list in terms of fatalities were falls from the platform, with overturns second. Hit by machine, vehicle or object was third, entrapment fourth and electrocution/electric shock fifth.

While numbers going up can be a result of better reporting or more MEWPs being used in the marketplace, it’s still concerning that the main causes of serious injury and death when using powered access machines haven’t changed in 10 years.

Industry experts and seasoned professionals debate why such accidents are still occurring.

Where accidents occur

Before looking into the factors influencing the number of accidents, it’s important to first look at where the accidents are occurring.

Sean Ward, national and accounts manager, U.S. and Canada, Haulotte, notes that many accidents occur in the arborist industry and close to overhead power lines.

Ebbe Christensen, president and CEO of Ruthmann Reachmaster, agrees, adding that the window cleaning segment and construction industry also experience a disproportional number of accidents.

If those working in tree care select a machine with a fibreglass basket in the mistaken belief it is an insulated aerial device, then this can also be a cause of electrocution incidents if occupants think they are isolated from contact with power lines.

Christensen adds that the tree care industry also tends to attract individuals with a high level of adrenalin-driven decision-making rather than evaluating the safety aspects.

“It all boils down to education and what level of education can you impose on an industry culture,” Christensen says.

Scott Owyen, director of training at Genie, says that his team has noticed significant accidents in the construction and industrial applications, large and small.

“Many of them own their own equipment, so they don’t have the benefit of a knowledgeable rental partner to educate them or provide training and technical support,” Owyen says.

Tony Groat, North America regional manager for IPAF, says that while the construction and tree care industries experience accidents because they are a major user of the equipment and need to work at height in hazardous locations, small businesses and occasional users also add to the overall accident count.

“They face the added challenges due to limited resources, lack of safety experiences or insufficient training programs,” Groat says.

Owyen adds to that sentiment by noting that “big box home goods stores rent MEWPs to anyone with no mention of training, fall protection, etc.”

Why accidents occur

Lack of emphasis on safety

Despite the adage “safety first,” Groat says many companies don’t place enough value on safety.

“Despite the slogan of safety being a priority, so are productivity, cost efficiency and other competing priorities,” Groat says.

Groat adds that the mentality of “find a way to get it done” is rewarded while “find a way to get it done safely” is punished.

The human factor

Christensen argues that human ingenuity is both people's best and strongest asset and at the same time, their worst enemy.

“Looking at recent years’ MEWP accidents, it is clear that human error rather than equipment failure is the root cause for accidents,” Christensen says. “The human factors are not just present, but they are the indisputable biggest factor in accidents prevention and safe operation.”

Christensen says that training and education at all levels of an organization are key.

“The main reason for human error is lack of knowledge one way or the other,” Christensen says. “It all drops down to having proper knowledge about the equipment, how to evaluate its condition, the worksite, the application and the proper use of the right equipment for the right job.”

In addition to a lack or training or education, a lot of human error can boil down to not planning properly, distractions and a rush to complete the work, according to Groat.

“Human factors that can impact an accident include being overtired, complacency, lack of situational awareness or attitudes such as ‘I’m not afraid to do that,’” Groat says.

Randy De Coteau, product safety engineer, Genie, says poor judgement is also to blame.

“Many of the incidents that I see are not so much error but poor judgement or complete disregard for proper use of the machine and safety,” De Coteau says.

Pat Schmetzer, director, product training and risk management at MEC Aerial Work Platforms, says human error also comes from lack of preoperational risk assessment, undue risk training and insufficient personal protective equipment.

Schmetzer also argues that due to the labor shortage, companies are hiring in operators who aren’t qualified to perform the job in the first place

“Operators lack the necessary skills and experience, and in many cases, (companies) are ‘scraping the bottom of the barrel’ for talent,” Schmetzer says.

Insufficient training

Untrained or inadequately trained operators should be reiterated as a root cause of accidents, Owyen says.

“Much of the time, it is because the operator has not received adequate training, if any," Owyen says. "Untrained supervisors also play a role when they direct an individual to perform an unsafe act to get the job done, often without being aware of the danger they are placing the operator in.”

Owyen says that Genie provides safety courses for operators who may have never had actual training.

“The information they receive astonishes them, as they have been performing unsafe acts for years without knowing any better, often at the direction of their supervisor,” Owyen says.

He adds that although the new ANSI A92 standards require MEWP Supervisor Training, most organizations are still unaware of that requirement, and some choose to ignore it completely.

Kevin O'Shea, director of safety at Hydro Mobile, agrees that safety is not always a priority at companies.

“Rental companies sometimes take a ‘bare-bones’ approach to training and familiarization,” O'Shea says.

Standards and regulations

When it comes to the question of whether current standards and regulations are sufficient, the experts are split.

On one side, De Coteau says standards and regulations have set a good bar for safety.

On the other hand, O'Shea notes that standards are not regulations, so it’s difficult to persuade all users to address responsibilities consistently.

“Most companies look at OSHA as something they have to comply with, but anything more (ANSI, safety and technical guidance documents, etc.) is seen as unnecessary and costly,” O'Shea says.

Groat agrees, noting that OSHA regulations are the minimum legal requirements for safety and that while OSHA regulations for MEWPs were written in the 1970s, industry standards are required to be reviewed every five years.

“The ANSI/SAIA A92 standards provide additional or more specific requirements and safe practices for MEWP use, and many go beyond OSHA requirements,” Groat says. “As OSHA regulations are enforceable by law and compliance is mandatory, standards are generally voluntary, and compliance with them will be more demanded when a lawsuit commences.”

Groat also cites a statistic from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), stating that the number of workplace fatalities in the U.S. has decreased from approximately 14,000 per year in 1970 to around 5,000 per year in recent years.

“(Standards) do work but require employer leadership to place a real value that is adopted by all employees as the only accepted outcome,” Groat says.

Schmetzer says that while standards adequately address the risk, specific regulations (OSHA) are outdated, lacking specifics and are confusing even to compliance officers. He also notes that its only enforcement tools are Section (5)(a)(1) General Duty Clause or “Incorporation by Reference,” which is seldom used.

Owyen thinks the challenge arises when it comes to getting the word out that the standards have changed.

“There is a lot of excellent supporting documentation regarding the requirements, but the information is not getting to the right people (owners, dealers, users, operators),” Owyen says.

Ward posits that until the latest ANSI is adopted and published widely, there is a gap between OSHA regulations and industry standards that cause MEWP user confusion over safe-use requirements. He adds that corporate manslaughter in the U.K. — stating that companies and organizations can be found guilty of corporate manslaughter as a result of serious management failures — was a game-changer for safety there.

When it comes to enforcement, Schmetzer says that OSHA’s enforcement or penalties do not provide sufficient motivations for employers to comply, and the process of enforcement and the issuing of fines and citations drags out too long to be effective.

Owyen somewhat agrees, noting that the threat of a penalty does little to persuade companies until they actually receive one.

Christensen thinks that current regulations and standards would do a better job of reducing accidents if accidents were monitored and penalties were better enforced.

“In many cases, there is no formal monitoring from a regulatory point of view, and it is up to the players to both interpret and follow the rules,” Christensen says.

Christensen says it is logical to look at other markets with frequent use of MEWPs and compare regulations and standards.

“When looking at Europe, we will see that there is both a culture, tradition and appetite for stronger government involvement and control in all aspects of life. I spent the first 28 years of my life there, so I speak not just from theory, but practical experience,” Christensen says. “The Europeans find it much more acceptable that there are laws and rules for everything, and as such, they have implemented much stricter regulations and standards.”

Seen from that angle, Christensen says that the U.S. regulations and standards can appear somewhat lax and inefficient, but from a culture point of view, Americans are generally less in favor of regulations at the expense of what's considered personal freedom.

Christensen says that while the U.S. does have sufficient regulations and standards, the industry needs to advocate better observations of standards through education on one side and better enforcement on the other side.

“American culture leans toward achievement rather than punishment, but we need to push both sides to raise the overall professionalism in the industry,” Christensen says. “There is a gap not so much in the objective regulations and the standards as much as there is a gap between the people that observe and enforce them on both sides of the fence.”

The solutions

Technological advancements

Some experts believe technology advancements can help cut down on incidents. For example, O'Shea points to Live Line Defender, SiOPS or similar machanisms.

Schmetzer agrees: “We seem to be in a period where new safety innovations are emerging, especially addressing proximity to overhead electrical conductors as well as devices to ensure lanyard attachments.”

“Xtra Deck is a safety innovation addressing climbing on rails or other means to access tight overhead areas on scissor and booms, and various innovations designed to reduce entrapment and crushing injuries are emerging,” Schmetzer says.

Christensen says modern technology with CAN bus-operated systems allow for machinery that can react quicker than an operator.

“Today’s lifts are safer than ever before as the monitoring systems on the MEWPs take over a lot of the decision-making by only allowing active operation within the safe work envelope of the equipment,” Christensen says.

Christensen points to level sensors, load sensors, active monitoring of ground conditions (outrigger based equipment), anticollision systems, startup systems (where the lift runs an electronic safety check on all key components and connections to make sure all systems are go before operation is allowed), systems to ensure safety harnesses are properly attached, anemometers that will reduce extension of a lift, lightning warning systems, power line distance warning systems and more.

Owyen says while of the new design requirements in the ANSI standards, such as platform load sense and terrain sensors, may minimize the potential for a situation that could cause an accident, they should never even come into play with a well-trained operator.

De Coteau agrees:“There is no technology that will influence the safe operation of a machine more than a competent and attentive operator.”

Trainings

To ensure operators are property trained, Groat says that all operators should report to management and that management must ensure that they assign a qualified person to monitor operator performance and supervise their work.

“That individual must be trained as a MEWP supervisor who understands the rules and regulations that apply to MEWPs, the selection of the correct MEWP for the task, knowledge of the potential hazards associated with use of MEWPs and the means to protect against identified hazards,” Groat says.

In addition to more strigent operator training, Ward points to stricter management protocols, risk assessments and method statements as ways to prevent accidents.

Christensen says it comes down to establishing a healthy safety culture (overall) in a company.

“If there are not only very visual guidelines, but also execution of safe work mentality and operation, then a company can foster a natural focus on safety, multiplying the chances to develop efficient systems dramatically,” Christensen says. “So, it all starts with the end in mind, evaluation of all the links from start to finish and how you implement safety conscience in every link.”

Regulating bodies and associations

Some experts think that associations can do very little to enforce compliance.

“It has to be driven by the law,” Ward says.

Groat notes that if the key word is “enforcement,” that is a role for OSHA and laws.

“That requires industry standards to be adopted by reference into OHSA regulations,” Groat says. “Industry associations submit a proposal to OSHA to get the standards into the rulemaking process.”

Owyen says that OSHA’s compliance officers need to have a deep understanding of the ANSI standards that they reference and how to use them.

“If they don’t really understand them or are not familiar with them, there is a good chance that they will not enforce them,” Owyen says. “Creating a continuous flow of information on the standards may assist them in being more proactive rather than reactive when it comes to MEWP-related violations.”

O'Shea adds that the industry can lobby authorities, distribute best practice info, raise the standard of training and improve the quality and adoption of standards.

Schmetzer says that associations have the means to gather many industry safety professionals together to provide a unified focus on product safety without competitive pressures.

“Associations can be the conduit to other industry associations where a strong, forceful and consistent message can be delivered,” Schmetzer says.

Christensen agrees.

“I think there could be a better and more aligned cooperation between the industry and OSHA to create a more holistic approach to the goal of safety. We must never forget what is the goal and how we reach it,” Christesen says. “It is important that OSHA and OSHA rulings are based on competent decisions and industry knowledge. For that to happen, it is vital to establish a close cooperation between authorities and private enterprise that will allow for best practices to be based on realistic terms and realistically implemented.”

Christensen adds that associations and trade organizations need to find better common grounds to work together rather than compete on something as important as training and safety.

“I am not advocating for one single entity to conduct the training as a monopoly, but I am advocating for transparency for how training is provided,” Christensen says.

Reportings

O'Shea and Schmetzer point to IPAF’s Global MEWP Safety Report as a detailer of many metrics and indicators.

“The top source for this accident reporting is the IPAF Accident Reporting Data Summaries. Of course, this requires companies to report at a higher level,” Schmetzer says.

Groat notes that IPAF’s database has been in operation for more than a decade and that the industry can support it with individual company reporting.

“Accident reporting specific to MEWPs would be critical: data to identify issues and ongoing performance,” Groat says. “The more detail available, the greater ability to address the issues.”

Christensen says that more timely and precise these systems are, the better indicator for what causes the accidents.

“What would really make a difference is reporting of near-misses as well,” Christensen says. “The accident reporting system IPAF operates allows for this, and while it is not mandatory, it seems like there is growing understanding of the need for it. With the technology available today, including social media, we have a much better chance to collect data, and if addressed correctly, I am sure they will lead to better indicators of causes for accident.”

Attitudes

O'Shea says that mentalities such as “the can-do attitude” and “productivity over safety” are culprits in breeding a bad safety culture.

Schmetzer says companies must 100 percent commit to safety practices and adopt a zero-tolerance attitude.

“Operator safety must always trump deadlines and budgets, and operators, supervisors, on-site safety staff and all workers must be fully trained and committed to 100 percent compliance with standards and regulations, possibly with team awards for outstanding performance,” Schmetzer says.

In creating that culture, Christensen notes that nonoperating employees need to understand the safety rules as well as those who will be operating the equipment and that there should be a positive mentality toward safety.

“It’s always better to be safe than sorry, and you are not considered a 'whistle blower' if you report hazardous issues,” Christensen says. “Rather, you are a safe team player.” p