In a recent conversation about the asphalt industry with Charles Goodhart, Executive Director Pennsylvania Asphalt Pavement Association (PAPA), he said, "Our industry has historically been seen as the dumping ground for other industrial sectors who have a lot of something they want to get rid of, and don't know what to do with it."

There are a lot of examples, as in: ground up roofing shingles, sulfur, pulverized old tires, instances of asbestos was even used in some old mixes, and even more recently in the news the Florida state government is trying to make it legal to incorporate radioactive waste into their roads. Many have wondered if, and some have been hopeful that, waste plastic was next.

Strange Bedfellows

Depending on how you look at it, the marriage of asphalt and waste plastic is a bad one. On the one hand you have asphalt which is the MOST RECYCLED product in the U.S., and we already have such a preponderance of reclaimed asphalt pavements (RAP) that it often sits in massive unused piles, just waiting for state and federal regulations to allow more of it to be used. Production technology, mix design, and chemical rejuvenators are getting better all the time, diminishing the line between virgin and RAP mix qualities. Green Asphalt in New York boasts a process that can utilize 100% RAP mixes. And then on the other hand there is plastic.

The very concept of recycling plastic has come into serious question in the last few years, notably after a 2022 report issued by Greenpeace found that the amount of new plastics being broken down and reformed into a second use plastic fell to a record low of 5%. The actual threshold for a product to be considered "recyclable" is 30%, and plastic has never come close to this, peaking in 2014 at 9.5%. However, that number was artificially inflated because the United States shipped millions of tons of waste to China and simply counted it "recycled."

On top of that, the single-use plastics industry projects to nearly triple production by 2050. Ironically, it's the same year the National Asphalt Pavement Association targeted to reach net-zero emissions for our industry. Additionally, a 2021 report by the Canadian government revealed that the chemical process of recycling is so toxic, that it prohibits the relatively small amounts of recycled products to be turned into "food-grade" packaging, a huge market. Ultimately, the Greenpeace study detailed five major barriers to both mechanical and chemical plastic recycling:

- Extremely difficult to collect

- Virtually impossible to sort for recycling

- Environmentally harmful to reprocess

- Often made of and contaminated by toxic materials

- Not economical to recycle.

One might look at all these well documented and researched hurdles, and decide that the plastic problem might be better addressed on the production end, rather than on the recycling end. While that might be true, some still look at the literal mountains of waste plastic, and think, "I can fix him." However, there are real reasons the notion is explored.

A Real Fixer-Upper: Potential Benefits

Plastics aren't completely foreign to the asphalt industry, obviously, and so from another perspective it makes sense to explore the possibilities of reducing the cost of polymer modified asphalt binders, often required by DOTs in mix designs for high-traffic interstates and roads. These make pavements more resistant to damage done by heavy trucks and extreme weather conditions, and are most commonly made from the polymer styrene-butadine-styrene (SBS), an engineered virgin plastic.

According to the waste plastic study conducted by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), "The percentage of polymer-modified asphalt sales ranged from 11% to 14% of total asphalt binder sales from 2010-2021. Using 12% as a reasonable value, this estimation assumes a best-case scenario in which recycled plastics would completely displace virgin polymers in asphalt mixtures."

Reducing the costs of SBS would be a significant economic incentive for the industry to adopt waste plastic when you consider data from the National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT) shows that the typical costs (2022) for virgin SBS modified asphalt binder per US tonne was $1,060. Any process that could bring that number down would certainly be welcomed.

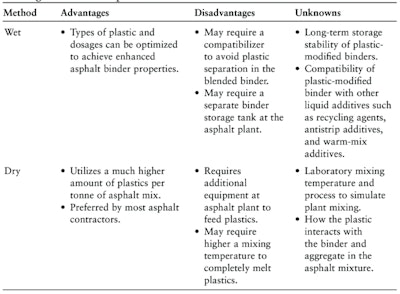

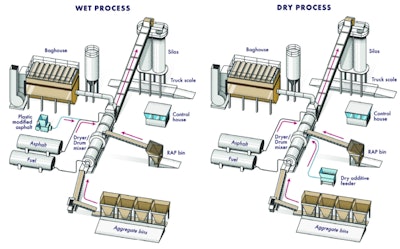

For comparison, the difference between virgin aggregate costs and RAP is about 50%. If a waste plastic version of SBS could provide a similar savings, it would monumental. Using waste plastic in this way is normally achieved by what is referred to as the "wet method," [see illustration at bottom page] but this often requires the use of a compatibilizer. Otherwise it risks separating into a highly viscous layer in the storage tanks.

Another theoretical benefit would be environmental. According to NAPA's head of sustainability, Joseph Shacat, an asphalt mix that contains 20% RAP reduces cradle-to-gate green house gas (GHG) emissions by 12%. Again, if something similar could be developed for SBS, it would be a big deal.

Any potential cost or ecological savings would be moot, however, if the quality and performance of the pavement were undermined. Lane cracking, rut depth, and pavement smoothness are all specific performance measure that the highway agencies took into account. Additional factors would be any potential harmful effects during the production or paving process on crews, the loss or contamination of RAP after milling, and potential toxic impacts like chemicall leeching or microplastic contamination of the surrounding environment.

It's Not Me, It's You

After conducting a massive literature review from field studies and lab testing in both the United States and other countries like China, India, UK, Australia, and more, who've documented experiments with post consumer plastics in asphalt, the NASEM report came away with the following results.

There have been large marketing campaigns and media coverage that suggested using recycled plastics in asphalt pavements would be a "win-win" and possibly act as a solution for both the environmental problems of waste plastics, while lowering costs and improving quality of mix designs. NASEM said despite these claims, "No evidence at this time supports the claims that the addition of recycled plastics will extend the life of asphalt pavements, and the purported cost savings have not been adequately documented."

While there are case studies and field experiments currently underway, it will be many years before they are completed and their data analyzed.

Perhaps, the most eye-opening conclusion was that the most optimistic estimate of plastic waste usage based on a dry process dosage rate of 0.5% by weight of mix used in a 12% of annual asphalt mix production would only use up ~240,000 tons of waste plastic a year. That might sound like a lot, but it is only 2.4% of current waste generated by the U.S. each year.

Also, a real blind spot for currently available research data is one of the most important. Almost no studies were underway to examine whether microplastics are generated from the normal use and wear of pavements surfaces that contain recycled plastics. These substances would greatly impact air quality and stormwater runoff into the environment.

Lastly, there is far too limited data available about the future recyclability of asphalt pavements that contain post consumer plastics from either wet or dry methods. Needless to say, if recycled plastics were to interrupt the current circularity and practically infinite recyclability of RAP, it would be the absolute death knell for this topic.

So You're Saying There's A Chance?

While attending the NAPA mid-year conference in July of 2023, one committee meeting briefly touched upon the topic of recycled plastics. For a moment it seemed that the topic would just breeze on by after some of the issues stated here were brought up. The seeming consensus at the table, and in the room, was pretty dismissive.

That is until one person in the room contested specifically the notion of such a small amount of waste reportedly being consumed. Although, the name of the individual speaking wasn't clear, they cited a field test in Colorado that used a "hybrid process" (something other than the wet or dry methods), and were able to consume fifteen metric tons of waste plastics for just a two mile stretch of road. This was a single anecdote given without documentation in the middle of a committee meeting from a person in the gallery, but if it holds real merit, then potentially there is still a pathway for waste plastics and asphalt to be together.

The final word hasn't been given yet on this issue, but the current outlook isn't good, especially as the asphalt industry is in the middle of a major transition on its own in regards to lower embodied carbon, EPDs, and performance based bidding (rather than simple low-cost bidding) are taking up most of the air in the room. These changes are here to stay for the foreseeable future, and if plastics eventually become a part of this more sustainable paradigm, that would be great for all parties involved.

![Img 1707[56]](https://img.forconstructionpros.com/files/base/acbm/fcp/image/2023/04/IMG_1707_56_.6437076c97961.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=191&q=70&rect=0%2C462%2C1920%2C1080&w=340)

![Glp Porsche 072723 465 64ee42287c29e[1]](https://img.forconstructionpros.com/files/base/acbm/fcp/image/2024/03/GLP_PORSCHE_072723_465.64ee42287c29e_1_.65e88b8589b9c.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=135&q=70&rect=0%2C520%2C2250%2C1266&w=240)