In concrete construction, few situations are more hazardous than a whipping concrete pumping hose.

A hose-whip is the sudden release of compressed air energy in the flexible hose(s) at the end of the delivery system. Three things are required to have a hose-whipping incident: Air in the concrete delivery system, a blockage in front of the air, and force behind the air to compress it. If the blockage is sufficiently hard to move, the air will compress by the force of the concrete coming behind it, storing the energy of the pump like a spring. Pressure rises until either a) the blockage is ‘blown out’ by the high pressure behind it, or b) the blockage is so complete that the pump reaches maximum pressure (determined by the pump manufacturer) without releasing the blockage. In this case, the blockage is known as a ‘plug.’ Plugs can only be removed by manual methods.

In the case of b), the hose whip doesn’t happen; concrete just stops emerging from the delivery system. The operator can reverse the pump to remove pressure, then find and dislodge the plug manually—without danger to anyone. If, however, situation a) is encountered, the compressed air will release all at once as the blockage is removed by force. That rapidly-decompressing air releases enough stored energy to cause the flexible hose to recoil in any direction. The hose has so much mass when filled with concrete that the whipping action is extremely hazardous. Understanding the causes of hose-whipping and receiving the appropriate training before working with and around a concrete pump can be the difference between a routine pour and a fatal injury.

“It’s one of the most litigious things that could happen on your jobsite tomorrow,” says pumping-industry safety expert Rob Edwards. Cases have settled in the tens-of-millions of dollars, and families are torn apart by an injury to a breadwinner.

Edwards has been in the pumping industry since 1978. He started as an operator, but moved to Schwing and eventually wrote the ACPA’s Safety Manual, much of the ACPA’s training materials, and chaired the subcommittee of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) dealing with the American National Standard for concrete pump and conveyor safety, ASME B30.27. He taught the ACPA safety seminar he co-authored for 25 years.

With the amount of potential danger involved, you cannot overstate the importance of safety. The circumstances leading to a hose-whipping incident happen almost every day on every job, but the incidents are still quite rare—in the vast majority of cases, air moves through the pipeline and escapes with few clues that it even happened. In that rare instance where air is in the line and the rocks line up just right to form a blockage, however, the incident is almost assured.

Hose-whipping is rare enough that a foreman may have been working with pumps for three years and never seen a hose-whip,” says Edwards. “The rule is that you never know if the circumstances will result in a whipping incident, but there are things you can do to be sure that an incident does not become an accident. If contractors are training on concrete pumping safety, hose-whipping is absolutely the number one thing that can happen—the other is electrocution.” (Editor’s Note: This article is focused on hose-whipping safety and does not cover boom pump electric safety.)

Raising Awareness of the B30.27 Safety Standard

With the goal of keeping every person on the jobsite safe, the American Concrete Pumping Association launched a major safety campaign to bring heightened awareness of ASME B30.27, the Safety Standard for Material Placement Systems (concrete pumps and concrete conveyors). The campaign highlights the responsibilities of each trade working with or around a concrete pump under the standard.

“The ACPA saw an industry need to ensure that everyone on the job site has a clear understanding of their responsibilities under the ASME B30.27 standard,” says Christi Collins, executive director for the ACPA and member of the association’s Job Site Safety Committee. “Our goal of this campaign is to encourage partnering across all the trades because, when we all work together, we create a safer environment for everyone.”

The organization developed and launched the microsite, WeAreSaferTogether.org to provide and promote valuable information to all who work with or around concrete pump equipment. The microsite serves as an educational resource to familiarize all parties with the standard and provides videos, downloadable flyers, job site responsibilities by trade, FAQs and much more. The American Society of Concrete Contractors, Concrete Foundations Association, Tilt-Up Concrete Association, and concrete contractor Joseph J. Albanese have pledged their support.

What Is Hose-Whipping?

For a concrete pump, work starts at the hopper where large hydraulic cylinders with rubber rams work in reciprocity. When one cylinder reaches the end of its travel, the concrete valve switches. This causes the concrete that had been flowing from the hopper to become concrete flowing into the pipeline. With a vigilant set of eyes at the pump, this could continue all day without incident but there are some things that happen every day on a pour that can lead to air becoming trapped in the pipeline.

“This is not a very common thing,” reminds Edwards. “If [the pipeline] was all concrete, hose-whipping wouldn't be an issue because concrete isn't compressible and cannot store energy. If a blockage formed in a line containing only concrete, the engine would grunt and then the blockage would release without whipping—maybe give a little wiggle— or plug so completely that concrete stops moving and manual remedies are needed. But because of the air, you're storing all the energy of pushing that concrete with the compressed air; the air pocket becomes a giant spring.”

This action can result in serious or even fatal injuries. The ACPA provides an example of a hose-whipping incident online (below), recorded October, 2002.

“Anytime there's a concrete pump pumping— even if it's a trailer pump and all the hoses are laying on the ground—a whip can and has happened,” says Edwards. “If you happen to be holding one and it whips, you may regret it for the rest of your life.”

What Causes Hose-Whipping?

As stated earlier, three things are required to have a hose-whipping incident: air in the concrete delivery system, a blockage in front of the air, and force behind the air to compress it. There are five ways air can enter a concrete pump placing system.

- Stopping the pump with one or more sections of the boom in a downward position—where gravity causes concrete to dribble out, and the equivalent volume of air enters

- Disconnection of extension hoses and/or the pipeline—anytime the line is opened, air is introduced

- Removal of a blockage or plug from the line introduces air into the line

- Reversal of the flow—reversing the concrete pump pulls air into the line

- The level of concrete in the hopper gets so low that the pump sucks air instead of concrete

American Concrete Pumping Association

American Concrete Pumping Association

Water priming is when the operator uses water as the lubricant. The ACPA does not recommend this process, however, because it can cause blockages in some cases. Still, it is a common practice in certain areas of the country due to the round, smooth quality of the local aggregates.

Edwards explains: “In some parts of the country like Seattle and Minneapolis—any place that they've got a lot of river stone as opposed to crushed aggregate—the finest sand is round. The medium sand is round. The larger sand is round. The rocks are round because they've been tumbled in a river for 100 million years making it easy to pump. A lot of these places overdo it on the cement which helps the strength and helps the ability to water prime because there's enough cement in the in the mix to coat the pipes without creating a blockage. Once the pipe is coated, then the mix will flow through the pipe regardless of how the pipe was primed.”

However, the first concrete coming out of a ready-mix delivery truck is likely to be rocky. Roughly a wheelbarrow full of gray colored rocks emerge from the mixer first. They’ve been in the mix long enough to be colored gray, but they are not part of the homogenous mix that’s called concrete. "Gray colored rocks won’t pump worth a darn," Edwards warns.

Aside from the primer, these rocks will be the first materials flowing through the pipeline. Once the material hits the apex of the boom, it starts to fall from gravity. Because of that, it doesn’t coat the inside of the pipe uniformly, leading to dry spots in the pipes on the downward side of the apex. The primer cannot go into the form because it’s not homogenous concrete, and even if you squirt out a couple of strokes of primer, the pipe won’t be uniformly coated until concrete runs steadily from the end hose.

“At that point, before concrete is running steadily out of the hose, no one should be near the hose,” warns Edwards. “That’s the only tool in our toolbox to completely avoid this hazard. You can pump for two weeks without ever seeing a whipping incident, or you could have two hose-whipping incidents today. While some conditions make a hose whipping incident more likely, there doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason for exactly when it happens.”

Back at the pump, should the hopper become low, concrete can create a fountain of sorts within a single stroke because of the compressed air shock when the valve switches to push concrete. This can cause an eruption and cover the area—sometimes large enough to even splash the ready mixed concrete truck. Even if the driver notices the air being sucked in and refills the hopper as fast as they can, there’s now a good chance that compressed air is trapped in the pipeline, where it will remain until it emerges from the end hose.

Warning labels placed on the machine by the manufacturer state that if any air enters the material cylinders for any reason and you can’t get the operator’s attention—hit the emergency stop.

“Depending on how fast you’re pumping, it can take a minimum of 5 to 10 seconds or a maximum of 30 seconds for the air to get all the way through,” says Edwards. “You have some time. You saw that it happened. And now you can warn everybody before it becomes an accident.”

Train for Safety

Training, good communication with the operator, and everyone focused on safety is the best recipe for getting everyone home safely at night.

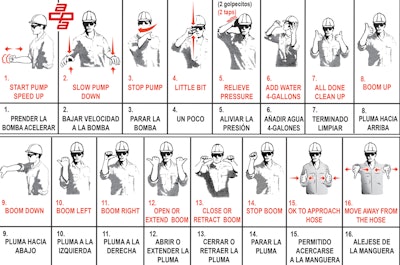

Aside from radios, the operator and placement team have a set of easy-to-understand hand signals to communicate. The two most vital are “move away from the hose” (thumbs pointed down moving away from each other) and “ok to approach hose” (thumbs pointed up with hands moving toward each other).

Learn the ACPA's safety hand signals for concrete pump operators and workers onsite.American Concrete Pumping Association

Learn the ACPA's safety hand signals for concrete pump operators and workers onsite.American Concrete Pumping Association

According to the ACPA Safety Bulletin Hose Whipping: Part II, “Whenever the pump is stopped for longer than a few minutes, the operator should have all personnel move a reasonable and prudent distance from the discharge hose or, when not practical, move the boom away from the pour to a safe location and re-establish flow before moving the boom back to the pour.”

When instructed to move away, all personnel should respond in kind with a minimum 1:1 ratio based on the length of the end hose. However, material could come out at high velocity, so Edwards recommends teams back away even further, if possible, and turn away from the hose. Put simply, if the end hose is 12 ft. long, placement teams need to back away at least 12 ft. and preferably more to account for pressurized material being expelled from the hose.

Concrete Pumping Placement Team Safety 101:

- Familiarize with the ASME B30.27 safety standard: Visit wearesafertogether.org for additional resources

- Wear the necessary PPE: hardhat/helmet, safety vest, finishers boots, work gloves (rubber), safety glasses, and mask (for dust protection)

- Follow the pump operator’s signals: everyone should understand the hand signals

- Include safety reminders in each morning’s safety meeting

- Have a phone available to call 911

- Know the address of the jobsite, have this at the ready

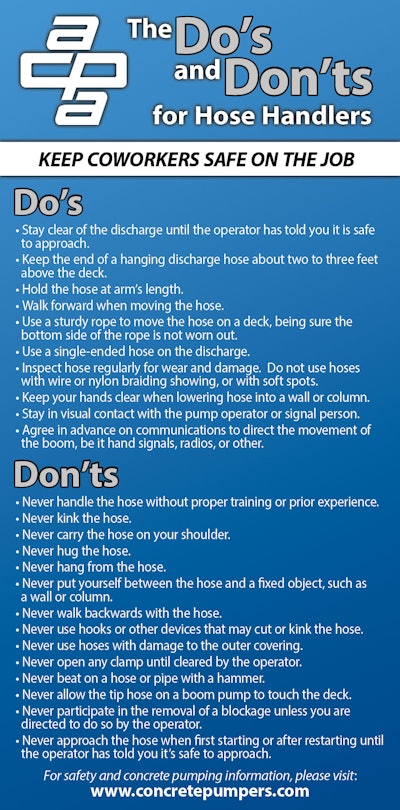

The ACPA has developed materials for concrete contractors working with and around concrete pumps. They have a list of “dos and don’ts” for hose handlers, provide safety bulletins, statements, and insight into ASME B30.27 Safety Standard. Additional training resources for both the operator and the placing crew can be obtained by calling (614-431-5618).

“If you call the ACPA, and say, ‘Please send me one of everything that talks about hose-whipping,’ you would get a lot of material,” says Edwards. “When we train the operators, we train them about how to keep the co-workers on the jobsite safe. When we train co-workers, we talk about the deadly hazard that this is.”

For Edwards, training is the key to safety. “If the crew and the operator have been trained, it's very rare to see a hose-whipping incident turn into an accident with injury. But if anybody in the process is untrained, it gets a lot more likely.”

He recommends having a safety meeting in a classroom setting where videos can be shared, and materials can be passed out. “If you take half an hour on the first day and then touch base at a safety reminder meeting each morning, it should keep the information fresh in the minds of the crew.”

Hose-whipping can be a dangerous situation, but safety conscious minds, trained placing crews, and certified pump operators can all factor in to lessen the chance. Failing that, results can be catastrophic.

Editor's Note: A special thank you to concrete pumping safety expert Rob Edwards for his contributions to this article.

Resources:

ASME B30.27 can be purchased at ASME.org/codes-standards/find-codes-standards/b30-27-material-placement-systems

The Do's & Don'ts for the Hose Handler: concretepumpers.com/sites/concretepumpers.com/files/attachments/dos_donts_hose_handler.pdf

Safety Bulletin, Part 1: concretepumpers.com/sites/concretepumpers.com/files/attachments/sb_hosewhipping_part1_0.pdf

Safety Bulletin, Part 2: concretepumpers.com/sites/concretepumpers.com/files/attachments/sb_hosewhipping_part2_0.pdf

The Most Hazardous Stroke of the Day: concretepumpers.com/sites/concretepumpers.com/files/attachments/safety_bulletin_most_hazardous_stroke.pdf

B30.27 FAQs: concretepumpers.com/sites/concretepumpers.com/files/attachments/asme_b30.27_faqs_0.pdf

Coworker Safety & Hose Handling: concretepumpers.com/content/coworker-safety-and-hose-handling-english

Many ACPA resources are also available in Spanish.