By Larry Stewart, Editor, ForConstructionPros.com

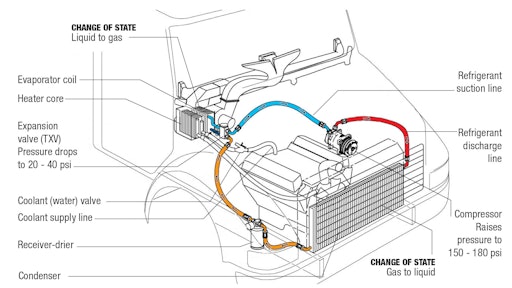

Keeping equipment operators productive as summer comes on requires an air conditioning system maintained to harness some cool physics. Most of the maintenance is pretty simple, but knowing how and where refrigerant phase-shifts between gaseous and liquid states can make diagnosing problems pretty straightforward.

The basics are essential

As with most equipment-system maintenance, the most profitable AC system maintenance usually masquerade as mundane housekeeping.

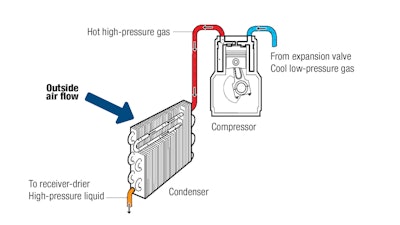

Ask Robert Brocx, technical steward (his actual title) at mobile air-conditioning-system maker Red Dot Corp., how to prevent the most-common failure modes for air conditioning, and he doesn’t hesitate: “Just keeping the condenser clean and not plugged with debris, and the fins not folded over from high-pressure washing. Air conditioning refrigerant surfs the big heat-transfer potential at the borderline between its gaseous and liquid states. The compressor pressurizes gaseous refrigerant so that air blowing over the condenser will condense it into liquid state.

Air conditioning refrigerant surfs the big heat-transfer potential at the borderline between its gaseous and liquid states. The compressor pressurizes gaseous refrigerant so that air blowing over the condenser will condense it into liquid state.

“It’s pretty typical to get some hydraulic fluid or oil on the condenser,” Brocx adds. A hose rupture or simple leak that makes its way into the air flow can coat the coolers. “It doesn’t look so bad, but it does impact the heat rejection of that condenser quite a bit.”

Oil’s a bit of a problem on its own, but it’s not alone for long in off-road conditions.

“It catches dust, and then you’ve got an insulating dust-and-oil mix on the fins so you’re not getting good heat transfer. And it also blocks some air flow.”

Reversing fans in today’s new equipment help clear dry debris from condensers and coolers, but they’ve got limitations, particularly if there’s oil residue pasting dirt to the fins.

Staying on top of this perennial problem isn’t rocket science. Somebody has to inspect condensers and other coolers regularly, and make sure they’re clean.

“The main thing is to look at the condenser coil regularly,” Brocx says. “If it does have oil on it, check to see if it’s refrigerant oil. That indicates a refrigerant leak; and it’s a very bad thing [for the air conditioning system].” When the expansion valve allows line pressure on the way to the evaporator to drop, the refrigerant heads back toward gaseous state and absorbs a lot of heat from warm cab air in the evaporator to complete the change.

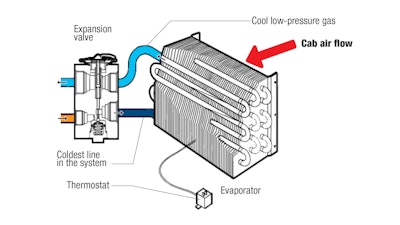

When the expansion valve allows line pressure on the way to the evaporator to drop, the refrigerant heads back toward gaseous state and absorbs a lot of heat from warm cab air in the evaporator to complete the change.

Brocx mentions maintaining the cab-air filters as a second priority. They’re seldom as easy to check as the condenser, but poor filter maintenance can cut an operator’s productivity even if the day is not terribly hot.

“Typically there are two: a fresh-air filter and a recirculated air filter,” Brocx explains. “Cab pressurization testing is done with clean filters. Once those filters start to plug up, 1) you reduce total air flow; and 2) you change your fresh- and recirc-air balance.

“Usually vehicle cabs are designed to have roughly 25 cfm of filtered fresh air coming into the cab. That helps 1) with keeping the operator alert – the oxygen in the fresh air displaces the CO2 content in the cab; 2) keeping the cab slightly pressurized; and 3) when it’s cold outside, that fresh air keeps cab air from getting so humid that it fogs the inside of the windows.”

Again, frequency of filter maintenance depends on operating conditions. Discovering the right frequency for your machines is worth studying to determine an effective maintenance interval. It’s important to have replacement filters on hand when they’re needed.

“Sometimes people just remove the filters when they’re dirty without replacing them, but then dust is going to go right to the evaporator,” Brocx warns. “Because the evaporator’s wet [you’ve seen condensate draining out of the systems], the dust is attracted to it and the inside of the evaporator just becomes a big mud ball. It will reduce air flow and really impact the cooling capacity of the system.”

Finding refrigerant leaks

The third air-conditioning maintenance priority is identifying refrigerant leaks. Most equipment uses O-ring fittings. Vibration and impact working off-road is far more stressful for those joints than for those in an on-road vehicle. Over time, they tend to leak.

“You’ll be able to see that because where the refrigerant is leaking, usually you will get a moist spot and then it will attract dust,” Bocx says. “So you’ll get a fitting just covered in dust. Sometimes you can see that it’s oily. If you have oily dust at a fitting, you can be pretty sure that’s leaking.”

Most OEMs put a UV- fluorescent dye into the refrigerant oil they use in their AC systems. A technician wearing protective eyewear designed to enhance ultraviolet light can trace the system with an ultraviolet light and where it hits refrigerant oil, it will glow.

“Harbor Freight has a pretty good UV light for about $5 – as good as the $120 light I have. In fact, I like it better because it’s brighter,” Bocx says.

“When you fix a leak, you really need to clean up that area [with soap and water or a product called Glow Away] so the next person doesn’t think there’s a leak there again.”

Diagnostics by touch

Air conditioning works by manipulating the state of the refrigerant, applying and releasing pressure, cooling it in the condenser and warming it in the evaporator. Air conditioning delivers its value by making sure liquid refrigerant changes to a gaseous state in the evaporator. It starts that process by releasing high-pressure liquid refrigerant through a tiny orifice into the line to the evaporator.

It is possible to learn about how well the AC system is working by cranking up the climate controls to max cool and air flow, and carefully touching some points in the system. In the lines just downstream from the evaporator’s pressure drop, the refrigerant approaches the transition to its gaseous state and becomes as cold as it will get in a typical AC system.

“Generally, the inlet to the expansion valve is going to be about 10 or more degrees F warmer than the ambient air. And directly across the expansion valve, the inlet to the evaporator (usually it goes through a small manifold) should be very cold,” Bocx says. “If it’s not cold right there, there’s a big problem; it might be that the expansion valve is not opening up.”

Low-pressure gas coming out of the evaporator should be about the same to 3 deg. F warmer than the inlet. The pressure drop through the evaporator and expansion-valve-controlled superheat pretty much cancel each other out, making the evaporator inlet and outlet close to the same temperature in a properly functioning system.

“If the outlet is 7 or more degrees warmer than the inlet, then the system’s probably low on refrigerant. If it’s 10 degrees warmer, either your expansion valve is bad or you’re low on refrigerant.”

Leaks demand more than a recharge

When you suspect an AC system charge is low, confirming and correcting the problem is simple but not always intuitive. To confirm that a system is low, a certified tech should recover the refrigerant, weigh it and compare the amount to the OEM’s specification for the amount required for a full charge.

“If the amount you recovered is significantly less, you know there’s a leak and can be pretty sure that it’s the low refrigerant charge causing the problem,” says Brocx.

“You should always replace the receiver-drier when you have a leak because when refrigerant leaves through a leak, moisture is always going in. System pressure doesn’t prevent moisture from traveling into the system. That’s like the No. 1 enemy inside the AC system.”

In fact, moisture ingression through hoses is one reason AC systems have receiver-driers. The rate of ingression is usually so slow that you don’t have to worry about it, but a leak will overwhelm the drier’s capacity.

Because the AC system manipulates very specific internal pressures to get the desired change of state where it is required, charging the system should be done carefully. System manufacturers prescribe a specific weight of refrigerant for each system they design, and recharging with just that weight is how a technician knows a system is charged accurately.

“The sight glass, most commonly located on receiver-drier, used to be a better indicator of system charge with R12 refrigerant and mineral oil because they were very miscible. But [today’s] R134a and PAG oil, under very high pressure, can look a little milky, like when R12 was low on charge. But it just indicates that the oil and refrigerant are not mixing as well as the mineral oil and the R12 did.

“Actually, ‘milky’ isn’t quite the right word for the appearance of R134a. At high pressures, the oil and refrigerant don’t mix as well, so you see streakiness or stuff going past the sight glass. Sometimes it’s just clear like water; that’s usually at a moderate pressure like 150 psig. If the system goes to 250 psig, then it starts to look streaky. You see things going through there, and it looks like it’s low on charge. If you keep adding charge, that’s just going to make the streakiness worse. Pressure’s going to keep increasing and the system’s going to be overcharged.”

Any time the condenser fan or compressor cycles – sometimes even when engine speed changes – refrigerant-vapor bubbles can be seen going by the sight glass.

Brocx still uses the sight glass as part of his charging process, but he weighs the refrigerant going in as the primary indicator of charge.

“I think a sight glass is a great thing, as long as you know what’s happening. If you’re checking on some other factors too – like the temperature at the vents in the cab or pressures in the system – the sight glass becomes just one more factor showing you what’s going on in the system.”

Is the heat really off?

Finally, Brocx says warm air mysteriously coming from the vents in the cab may just require you doublecheck that the coolant, or water, valve isn’t leaking. During cooling season, the water valve should be shut off completely.

“On most construction equipment, all the cab air flows through the evaporator and then through the heater core.”

Coolant circulating through the heater core will be about 180 deg. The AC system’s refrigerant can only be cooled down to about 32 deg., so the air leaving the evaporator might be 45 deg. Run that through a 180-deg. heater core, and air might be coming out of your vents at 60 or 70 deg.

“Watch out if the AC system works really well when the engine is cold, but seems to stop cooling when the engine warms up. If the pipe coming out of the TXV [expansion valve] is still cold, most likely the water valve is leaking. That’s one that comes up quite a bit.”